Silicon dioxide

| Silicon dioxide | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Preferred IUPAC name

Silicon dioxide

|

|

|

Silanedione

|

|

|

Other names

Quartz

Silica |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 7631-86-9 (anhydrate) |

| PubChem | 24261 (anhydrate) |

| ChemSpider | 22683 (anhydrate) |

| EC number | 231-545-4 |

| KEGG | C16459 |

| MeSH | Silicon+dioxide |

| ChEBI | 30563 |

| RTECS number | VV7565000 |

| Gmelin Reference | 200274 |

|

SMILES

O=[Si]=O

|

|

|

InChI

InChI=1S/O2Si/c1-3-2

Key: VYPSYNLAJGMNEJ-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | SiO2 |

| Molar mass | 60.0843 g/mol |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Density | 2.634 g/cm3 |

| Melting point |

1650(±75) °C |

| Boiling point |

2230 °C |

| Solubility in water | 0.012 g/100 mL |

| Related compounds | |

| Other anions | Silicon sulfide |

| Other cations | Carbon dioxide Germanium dioxide Tin dioxide Lead dioxide |

| Related silicon oxides | Silicon monoxide |

| Related compounds | Silicic acid "Silica gel" |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

The chemical compound silicon dioxide, also known as silica (from the Latin silex), is an oxide of silicon with a chemical formula of SiO2 and has been known for its hardness since antiquity. Silica is most commonly found in nature as sand or quartz, as well as in the cell walls of diatoms. Silica is the most abundant mineral in the Earth's crust.[1][2]

Silica is manufactured in several forms including fused quartz, crystal, fumed silica (or pyrogenic silica, trademarked Aerosil or Cab-O-Sil), colloidal silica, silica gel, and aerogel. In addition, silica nanosprings are produced by the vapor-liquid-solid method at temperatures as low as room temperature.[3]

Silica is used primarily in the production of window glass, drinking glasses, and beverage bottles. The majority of optical fibers for telecommunications are also made from silica. It is a primary raw material for many whiteware ceramics such as earthenware, stoneware, porcelain, as well as industrial Portland cement.

Silica is common additive in the production of foods, where it is used primarily as a flow agent in powdered foods, or to absorb water in hygroscopic applications. It is the primary component of diatomaceous earth which has many uses ranging from filtration to insect control. It is also the primary component of rice husk ash which is used, for example, in filtration and cement manufacturing.

Thin films of silica grown on silicon wafers via thermal oxidation methods can be quite beneficial in microelectronics, where they act as electric insulators with high chemical stability. In electrical applications, it can protect the silicon, store charge, block current, and even act as a controlled pathway to limit current flow.

A silica-based aerogel was used in the Stardust spacecraft to collect extraterrestrial particles. Silica is also used in the extraction of DNA and RNA due to its ability to bind to the nucleic acids under the presence of chaotropes. As hydrophobic silica it is used as a defoamer component. In hydrated form, it is used in toothpaste as a hard abrasive to remove tooth plaque.

In its capacity as a refractory, it is useful in fiber form as a high-temperature thermal protection fabric. In cosmetics, it is useful for its light-diffusing properties and natural absorbency. Colloidal silica is used as a wine and juice fining agent. In pharmaceutical products, silica aids powder flow when tablets are formed. Finally, it is used as a thermal enhancement compound in ground source heat pump industry.

Contents |

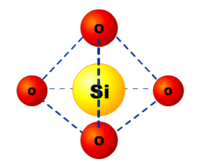

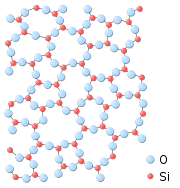

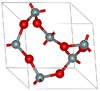

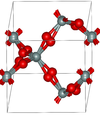

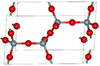

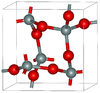

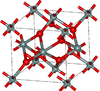

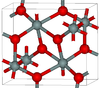

Crystal structure

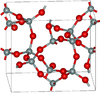

In the vast majority of silicates, the Si atom shows tetrahedral coordination, with 4 oxygen atoms surrounding a central Si atom. The most common example is seen in the quartz crystalline form of silica SiO2. In each of the most thermodynamically stable crystalline forms of silica, on average, all 4 of the vertices (or oxygen atoms) of the SiO4 tetrahedra are shared with others, yielding the net chemical formula: SiO2- (this can be understood as each oxygen, which is bonded to 2 Si atoms contributes 1/2 to the stoichiometry).[4]

For example, in the unit cell of alpha-quartz, the central tetrahedron shares all 4 of its corner O atoms, the 2 face-centered tetrahedra share 2 of their corner O atoms, and the 4 edge-centered terahedra share just 1 of their O atoms with other SiO4 tetrahedra. This leaves a net average of 12 out of 24 (or 1 out of 2) total vertices for that portion of the 7 SiO4 tetrahedra which are considered to be a part of the unit cell for silica (see 3-D Unit Cell).

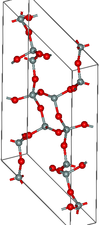

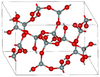

SiO2 has a number of distinct crystalline forms (polymorphs) in addition to amorphous forms. With the exception of stishovite and fibrous silica, all of the crystalline forms involve tetrahedral SiO4 units linked together by shared vertices in different arrangements. Silicon-oxygen bond lengths vary between the different crystal forms, for example in α-quartz the bond length is 161 pm, whereas in α-tridymite it is in the range 154–171 pm. The Si-O-Si angle also varies between a low value of 140° in α-tridymite, up to 180° in β-tridymite. In α-quartz the Si-O-Si angle is 144°.[6]

Fibrous silica has a structure similar to that of SiS2 with chains of edge-sharing SiO4 tetrahedra. Stishovite, the higher pressure form, in contrast has a rutile like structure where silicon is 6 coordinate. The density of stishovite is 4.287 g/cm3, which compares to α-quartz, the densest of the low pressure forms, which has a density of 2.648 g/cm3.[7] The difference in density can be ascribed to the increase in coordination as the six shortest Si-O bond lengths in stishovite (four Si-O bond lengths of 176 pm and two others of 181 pm) are greater than the Si-O bond length (161 pm) in α-quartz.[8] The change in the coordination increases the ionicity of the Si-O bond.[9] But more important is the observation that any deviations from these standard parameters constitute microstructural differences or variations which represent an approach to an amorphous, vitreous or glassy solid.

Note that the only stable form under normal conditions is α-quartz and this is the form in which crystalline silicon dioxide is usually encountered. In nature impurities in crystalline α-quartz can give rise to colors (see list).

Note also that both high temperature minerals, cristobalite and tridymite, have both a lower density and index of refraction than quartz. Since the composition is identical, the reason for the discrepancies must be in the increased spacing in the high temperature minerals. As is common with many substances, the higher the temperature the farther apart the atoms due to the increased vibration energy.

The high pressure minerals, seifertite, stishovite, and coesite, on the other hand, have a higher density and index of refraction when compared to quartz. This is probably due to the intense compression of the atoms that must occur during their formation, resulting in a more condensed structure.

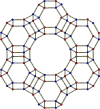

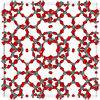

Faujasite silica is another form of crystalline silica. It is obtained by dealumination of a low-sodium, ultra-stable Y zeolite with a combined acid and thermal treatment. The resulting product contains over 99% silica, has high crystallinity and high surface area (over 800 m2/g). Faujasite-silica has very high thermal and acid stability. For example, it maintains a high degree of long-range molecular order (or crystallinity) even after boiling in concentrated hydrochloric acid.[10]

Molten silica exhibits several peculiar physical characteristics that are similar to the ones observed in liquid water: negative temperature expansion, density maximum, and a heat capacity minimum.[11] When molecular silicon monoxide, SiO, is condensed in an argon matrix cooled with helium along with oxygen atoms generated by microwave discharge, molecular SiO2 is produced which has a linear structure. Dimeric silicon dioxide, (SiO2)2 has been prepared by reacting O2 with matrix isolated dimeric silicon monoxide, (Si2O2). In dimeric silicon dioxide there are two oxygen atoms bridging between the silicon atoms with an Si-O-Si angle of 94° and bond length of 164.6 pm and the terminal Si-O bond length is 150.2 pm. The Si-O bond length is 148.3 pm which compares with the length of 161 pm in α-quartz. The bond energy is estimated at 621.7 kJ/mol.[12]

| Form | Crystal symmetry Pearson symbol, group No. |

Notes | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-quartz | rhombohedral (trigonal) hP9, P3121 No.152[13] |

Helical chains making individual single crystals optically active; α-quartz converts to β-quartz at 846 K |  |

| β-quartz | hexagonal hP18, P6222, No.180[14] |

closely related to α-quartz (with an Si-O-Si angle of 155°) and optically active; β-quartz converts to β-tridymite at 1140 K |  |

| α-tridymite | orthorhombic oS24, C2221, No.20[15] |

metastable form under normal pressure |  |

| β-tridymite | hexagonal hP12, P63/mmc, No. 194[15] |

closely related to α-tridymite; β-tridymite converts to β-cristobalite at 2010 K |  |

| α-cristobalite | tetragonal tP12, P41212, No. 92[16] |

metastable form under normal pressure |  |

| β-cristobalite | cubic cF104, Fd3m, No.227[17] |

closely related to α-cristobalite; melts at 1978 K |  |

| faujasite | cubic cF576, Fd3m, No.227[18] |

sodalite cages connected by hexagonal prisms; 12-membered ring pore opening; faujasite structure.[10] |  |

| melanophlogite | cubic (cP*, P4232, No.208)[5] or tetragonal (P42/nbc)[19] | Si5O10, Si6O12 rings; mineral always found with hydrocarbons in interstitial spaces-a clathrasil[20] |  |

| keatite | tetragonal tP36, P41212, No. 92[21] |

Si5O10, Si4O14, Si8O16 rings; synthesised from glassy silica and alkali at 600–900K and 40–400 MPa |  |

| moganite | monoclinic mS46, C2/c, No.15[22] |

Si4O8 and Si6O12 rings |  |

| coesite | monoclinic mS48, C2/c, No.15[23] |

Si4O8 and Si8O16 rings; 900 K and 3–3.5 GPa |  |

| stishovite | Tetragonal tP6, P42/mnm, No.136[24] |

One of the densest (together with seifertite) polymorphs of silica; rutile-like with 6-fold coordinated Si; 7.5–8.5 GPa |  |

| poststishovite | orthorhombic oP12, Pnc2, No.30[25] |

|

|

| fibrous | orthorhombic oI12, Ibam, No.72[26] |

like SiS2 consisting of edge sharing chains |  |

| seifertite | orthorhombic oP, Pbcn[27] |

One of the densest (together with stishovite) polymorphs of silica; is produced at pressures above 40 GPa.[28] |  |

Quartz glass

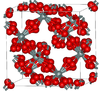

When silicon dioxide SiO2 is cooled rapidly enough, it does not crystallize but solidifies as a glass. The glass transition temperature of pure SiO2 is about 1600 K. Like most of the crystalline polymorphs the local atomic structure in pure silica glass is regular tetrahedra of oxygen atoms around silicon atoms. The difference between the glass and the crystals arises in the connectivity of these tetrahedral units. SiO2 glass consists of a non-repeating network of tetrahedra, where all the oxygen corners connect two neighbouring tetrahedra. Although there is no long range periodicity in the glassy network there remains significant ordering at length scales well beyond the SiO bond length. One example of this ordering is found in the preference of the network to form rings of 6-tetrahedra.[29]

Chemistry

Silicon dioxide is formed when silicon is exposed to oxygen (or air). A very shallow layer (approximately 1 nm or 10 Å) of so-called native oxide is formed on the surface when silicon is exposed to air under ambient conditions. Higher temperatures and alternative environments are used to grow well-controlled layers of silicon dioxide on silicon, for example at temperatures between 600 and 1200 °C, using so-called dry or wet oxidation with O2 or H2O, respectively.[30] The depth of the layer of silicon replaced by the dioxide is 44% of the depth of the silicon dioxide layer produced.[30]

Alternative methods used to deposit a layer of SiO2 include[31]

- Low temperature oxidation (400–450 °C) of silane

-

- SiH4 + 2 O2 → SiO2 + 2 H2O.

- Decomposition of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) at 680–730 °C

-

- Si(OC2H5)4 → SiO2 + 2 H2O + 4 C2H4.

- Plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition using TEOS at about 400 °C

-

- Si(OC2H5)4 + 12 O2 → SiO2 + 10 H2O + 8 CO2.

- Polymerization of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) at below 100 °C using amino acid as catalyst.[32]

Pyrogenic silica (sometimes called fumed silica or silica fume), which is a very fine particulate form of silicon dioxide, is prepared by burning SiCl4 in an oxygen rich hydrocarbon flame to produce a "smoke" of SiO2:[7]

- SiCl4 + 2 H2 + O2 → SiO2 + 4 HCl.

Amorphous silica, silica gel, is produced by the acidification of solutions of sodium silicate to produce a gelatinous precipitate that is then washed and then dehydrated to produce colorless microporous silica.[7]

Quartz exhibits a maximum solubility in water at temperatures about 340 °C.[33] This property is used to grow single crystals of quartz in a hydrothermal process where natural quartz is dissolved in superheated water in a pressure vessel which is cooler at the top. Crystals of 0.5–1 kg can be grown over a period of 1–2 months.[6] These crystals are a source of very pure quartz for use in electronic applications.[7]

Fluorine reacts with silicon dioxide to form SiF4 and O2 whereas the other halogen gases (Cl2, Br2, I2) react much less readily.[7]

Silicon dioxide is attacked by hydrofluoric acid (HF) to produce hexafluorosilicic acid:[6]

- SiO2 + 6 HF → H2SiF6 + 2 H2O.

HF is used to remove or pattern silicon dioxide in the semiconductor industry.

Silicon dioxide dissolves in hot concentrated alkali or fused hydroxide:[7]

- SiO2 + 2 NaOH → Na2SiO3 + H2O.

Silicon dioxide reacts with basic metal oxides (e.g. sodium oxide, potassium oxide, lead(II) oxide, zinc oxide, or mixtures of oxides forming silicates and glasses as the Si-O-Si bonds in silica are broken successively).[6] As an example the reaction of sodium oxide and SiO2 can produce sodium orthosilicate, sodium silicate, and glasses, dependent on the proportions of reactants:[7]

- 2 Na2O + SiO2 → Na4SiO4;

- Na2O + SiO2 → Na2SiO3;

- (0.25–0.8)Na2O + SiO2 → glass.

Examples of such glasses have commercial significance e.g. soda lime glass, borosilicate glass, lead glass. In these glasses, silica is termed the network former or lattice former.[6]

With silicon at high temperatures gaseous SiO is produced:[6]

- SiO2 + Si → 2 SiO (gas).

Sol-gel

The sol-gel process is a wet chemical technique used for the fabrication of both glassy and ceramic materials. In this process, the sol (or solution) evolves gradually towards the formation of a gel-like network containing both a liquid phase and a solid phase. The basic structure or morphology of the solid phase can range anywhere from discrete colloidal particles to continuous chain-like polymer networks.[34][35]

The term “colloid” is specific to the size of the individual particles, which are greater than atoms but small enough not to settle to the bottom of a container immediately. Their dynamic behavior is governed by forces of gravity and sedimentation, but may remain suspended in a liquid medium indefinitely. This critical size range (or particle width) typically ranges from tens of angstroms to a few microns.

- In basic solutions (pH > 7), the particles may grow to sufficient size to become colloids. Particles like these may become highly ordered in a manner similar to those seen in precious opal.

- Under acidic conditions (pH < 7), a more open continuous network of chain-like polymers is formed. Polymers like this can be useful due to their viscosity, which allows them to be drawn or spun from solution into fibers, or drawn as thin films into surface coatings. Such glass fiber is useful for guided lightwave transmission, with ceramic fiber providing excellent thermal insulation.

In either case, the sol evolves towards the formation of a 2-phase gel. In the case of the colloid, the number of particles in an extremely dilute suspension may be so low that a significant amount of solvent may need to be removed initially for the gel-like properties to be recognized. This can be accomplished in any number of ways. The simplest method is to allow time for sedimentation to occur, and then pour off the remaining liquor. A variable speed centrifuge can also be used to accelerate the process of liquid removal.

Removal of the remanent solvent phase requires a drying process, which is typically accompanied by a significant amount of shrinkage and densification. Since the water will most likely reside within microstructural pores, the rate at which the solvend can be removed is ultimately determined by the distribution of pore room in the gel. Subsequent thermal treatment (or low temperature sintering at 500–600 °C) may be performed in order to obtain a higher density product. With regard to methods of application:

- The sol can be deposited on a substrate to form a film using dip-coating or spin-coating;

- It can be cast into a suitable container with the desired shape;

- It can be used to synthesize fine high-purity powders.[36][37]

The sol-gel approach is a cheap and low-temperature technique that maintains a high degree of chemical purity. Thus it allows for total control of the product’s chemical composition. It can be used in ceramics manufacturing processes, as an investment casting material, or as a means of producing thin films or coatings.[38]

Sol-gel derived components have diverse applications in optics, electronics, energy, space, physical and chemical sensors, biosensors, controlled drug release in medicine, and chemical separation on a cellular level. Ceramic powders of a wide range of chemical composition can be formed by such techniques. The generation of particles uniform in size and shape was investigated extensively by Egon Matijevic and his co-workers. In the case of chromium, aluminum, and titanium salts, spherical particles were formed whereas particles of crystallographic symmetry resulted from solutions of copper and iron salts.[36][37][39][40][41][42][43][44]

In 1956, Kolbe described the formation of spherical silica particles in basic solution. The mechanisms of precipitation—and the chemical conditions that skew the structure toward linear or branched structures—are the most critical issues faced in the chemistry laboratory by sol-gel scientists. Again, these are the factors which will ultimately determine the form of the microstructure over a range of length scales in the green or unfired body. Factors, such as chemical acidity which lead to the formation of linear polymers (as opposed to particles), are ideal for the formation of spinnable solutions such as those used for the formation of thin films and coatings as well as optical quality fiber.

Biomaterials

Silicification is quite common in the biological world and occurs in bacteria, single-celled organisms, plants, and animals (invertebrates and vertebrates). Crystalline minerals formed in this environment often show exceptional physical properties (e.g. strength, hardness, fracture toughness) and tend to form hierarchical structures that exhibit microstructural order over a range of scales. The minerals are crystallized from an environment that is undersaturated with respect to silicon, and under conditions of neutral pH and low temperature (0–40 °C). Formation of the mineral may occur either within or outside of the cell wall of an organism, and specific biochemical reactions for mineral deposition exist that include lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates. Silica is a material strengthener of bone and can be fetched in the trace silicon compounds in beer.

Health effects

Inhaling finely divided crystalline silica dust in very small quantities (OSHA allows 0.1 mg/m3) over time can lead to silicosis, bronchitis, or cancer, as the dust becomes lodged in the lungs and continuously irritates them, reducing lung capacities. (Silica does not dissolve over time.) This effect can be an occupational hazard for people working with sandblasting equipment, products that contain powdered crystalline silica and so on. Children, asthmatics of any age, allergy sufferers, and the elderly (all of whom have reduced lung capacity) can be affected in much earlier. Amorphous silica, such as fumed silica is not associated with development of silicosis.[45] Laws restricting silica exposure with respect to the silicosis hazard specify that the silica is both crystalline and dust-forming.

In respects other than inhalation, pure silicon dioxide is inert and harmless. Clean silicon dioxide yields no fumes and is insoluble in vivo. It is indigestible, with no nutritional value and no toxicity. When silica is ingested orally, it passes unchanged through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, exiting in the feces, leaving no trace behind. Small pieces of silicon dioxide are also harmless as they do not obstruct the GI tract, if they are not jagged enough to scathe its lining.

A study which followed subjects for 15 years found that higher levels of silica in water appeared to decrease the risk of dementia. The study found that with an increase of 10 milligram-per-day of the intake of silica in drinking water, the risk of dementia dropped by 11%.[46]

See also

|

|

|

References

- ↑ Iler, R.K. (1979). The Chemistry of Silica. Plenum Press. ISBN 047102404X.

- ↑ Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition". Technology and Culture (Society for the History of Technology) 2 (2): 97–111. doi:10.2307/3101411. http://jstor.org/stable/3101411.

- ↑ Lidong Wang, D Major, P Paga, D Zhang, M G Norton, D N McIlroy (2006). "High yield synthesis and lithography of silica-based nanospring mats". Nanotechnology 17: S298–S303. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/17/11/S12.

- ↑ Kihara, K. (1990). "An X-ray study of the temperature dependence of the quartz structure". European Journal of Mineralogy 2: 63.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Skinner B.J., Appleman D.E. (1963). "Melanophlogite, a cubic polymorph of silica". American Mineralogist 48: 854–867. http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM48/AM48_854.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001), Inorganic Chemistry, San Diego: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, A. (1984), Chemistry of the Elements, Oxford: Pergamon, pp. 393–99, ISBN 0-08-022057-6

- ↑ Wells A.F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford Science Publications. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ↑ Kirfel, A.; Krane, H. G.; Blaha, P.; Schwarz, K.; Lippmann, T. (2001). "Electron-density distribution in stishovite, SiO2: a new high-energy synchrotron-radiation study". Acta Crystallographica A 57: 663. doi:10.1107/S0108767301010698.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 J. Scherzer (1978). "Dealuminated faujasite-type structures with SiO2/Al2O3 ratios over 100". Journal of Catalysis 54: 285. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(78)90051-9.

- ↑ Shell, Scott M.; Pablo G. Debenedetti, Athanassios Z. Panagiotopoulos (2002). "Molecular structural order and anomalies in liquid silica". Phys. Rev. E 66: 011202. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.66.011202. http://www.engr.ucsb.edu/~shell/papers/2002_PRE_silica.pdf.

- ↑ Peter Jutzi, Ulrich Schubert (2003). Silicon chemistry: from the atom to extended systems. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3527306471. http://books.google.com/?id=iRNDUz0F0rwC&pg=PP1.

- ↑ Lager G.A., Jorgensen J.D., Rotella F.J. (1982). "Crystal structure and thermal expansion of a-quartz SiO2 at low temperature". Journal of Applied Physics 53: 6751–6756. doi:10.1063/1.330062.

- ↑ Wright A.F., Lehmann M.S. (1981). "The Structure of Quartz at 25 and 590 °C Determined by Neutron Diffraction". Journal of Solid State Chemistry 36: 371–380. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(81)90449-7.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kuniaki Kihara, Matsumoto T., Imamura M. (1986). "Structural change of orthorhombic-I tridymite with temperature: A study based on second-order thermal-vibrational parameters". Zeitschrift fur Kristallographie 177: 27–38.

- ↑ Downs R.T., Palmer D.C. (1994). "The pressure behavior of a cristobalite". American Mineralogist 79: 9–14. http://www.geo.arizona.edu/xtal/group/pdf/AM79_9.pdf.

- ↑ Wright A.F., Leadbetter A.J. (1975). "The structures of the b-cristobalite phases of SiO2 and AlPO4". Philosophical Magazine 31: 1391–1401. doi:10.1080/00318087508228690.

- ↑ Hriljac J.A., Eddy M.M., Cheetham A.K., Donohue J.A., Ray G.J. (1993). "Powder Neutron Diffraction and 29Si MAS NMR Studies of Siliceous Zeolite-Y". Journal of Solid State Chemistry 106: 66–72. doi:10.1006/jssc.1993.1265.

- ↑ Nakagawa T, Kihara K, Harada K (2001). "The crystal structure of low melanophlogite". American Mineralogist 86: 1506. http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/AMS/minerals/Melanophlogite.

- ↑ Rosemarie Szostak (1998). Molecular sieves: Principles of Synthesis and Identification. Springer. ISBN 0751404802. http://books.google.com/?id=lteintjA2-MC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Shropshire J., Keat P.P., Vaughan P.A. (1959). "The crystal structure of keatite, a new form of silica". Zeitschrift fur Kristallographie 112: 409–413. doi:10.1524/zkri.1959.112.1-6.409.

- ↑ Miehe G., Graetsch H. (1992). "Crystal structure of moganite: a new structure type for silica". European Journal of Mineralogy 4: 693.

- ↑ Levien L., Prewitt C.T. (1981). "High-pressure crystal structure and compressibility of coesite". American Mineralogist 66: 324–333. http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM66/AM66_324.pdf.

- ↑ Smyth J.R., Swope R.J., Pawley A.R. (1995). "H in rutile-type compounds: II. Crystal chemistry of Al substitution in H-bearing stishovite". American Mineralogist 80: 454–456. http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/am/vol80/AM80_454.pdf.

- ↑ Belonoshko A.B., Dubrovinsky L.S., Dubrovinsky N.A. (1996). "A new high-pressure silica phase obtained by molecular dynamics". American Mineralogist 81: 785. http://www.minsocam.org/MSA/ammin/toc/Articles_Free/1996/Belonoshko_p785-788_96.pdf.

- ↑ Weiss A.; Weiss, Armin (1954). "Zur Kenntnis der faserigen Siliciumdioxyd-Modifikation". Zeitschrift fuer Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie 276: 95–112. doi:10.1002/zaac.19542760110.

- ↑ Dera P, Prewitt C T, Boctor N Z, Hemley R J (2002). "Characterization of a high-pressure phase of silica from the Martian meteorite Shergotty". American Mineralogist 87: 1018. http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/AMS/authors/Boctor%20N%20Z.

- ↑ Seifertite at Mindat

- ↑ Elliot, S.R. (1991). "Medium-range structural order in covalent amorphous solids". Nature 354

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Sunggyu Lee (2006). Encyclopedia of chemical processing. CRC Press. ISBN 0824755634.

- ↑ Robert Doering, Yoshio Nishi (2007). Handbook of Semiconductor Manufacturing Technology. CRC Press. ISBN 1574446754. http://books.google.com/?id=Qi98H-iTgLEC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ A.B.D. Nandiyanto; S.-G Kim; F. Iskandar; and K. Okuyama (2009). "Synthesis of Silica Nanoparticles with Nanometer-Size Controllable Mesopores and Outer Diameters". Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 120 (3): 447–453. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.12.019.

- ↑ Fournier R.O., Rowe J.J. (1977). "The solubility of amorphous silica in water at high temperatures and high pressures". American Mineralogist 62: 1052–1056. http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM62/AM62_1052.pdf.

- ↑ Brinker, C.J.; G.W. Scherer (1990). Sol-Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol-Gel Processing. Academic Press. ISBN 0121349705.

- ↑ L.L.Hench, J.K.West; West, Jon K. (1990). "The Sol-Gel Process". Chem. Rev. 90: 33–72. doi:10.1021/cr00099a003.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Matijevic, Egon. (1986). "Monodispersed colloids: art and science". Langmuir 2: 12. doi:10.1021/la00067a002.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Brinker, C. J.; Mukherjee, S. P. (1981). "Conversion of monolithic gels to glasses in a multicomponent silicate glass system". Journal of Materials Science 16: 1980. doi:10.1007/BF00540646.

- ↑ Klein, L. (1994). Sol-Gel Optics: Processing and Applications. Springer Verlag. ISBN 0792394240. http://books.google.com/?id=wH11Y4UuJNQC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Dislich, Helmut (1971). "New Routes to Multicomponent Oxide Glasses". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 10: 363. doi:10.1002/anie.197103631.

- ↑ Sakka, S; Kamiya, K (1980). "Glasses from metal alcoholates". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 42: 403. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(80)90040-X.

- ↑ Yoldas, B. E. (1979). "Monolithic glass formation by chemical polymerization". Journal of Materials Science 14: 1843. doi:10.1007/BF00551023.

- ↑ Prochazka, S.; Klug, F. J. (1983). "Infrared-Transparent Mullite Ceramic". Journal of the American Ceramic Society 66: 874. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb11004.x.

- ↑ Ikesue, Akio; Kinoshita, Toshiyuki; Kamata, Kiichiro; Yoshida, Kunio (1995). "Fabrication and Optical Properties of High-Performance Polycrystalline Nd:YAG Ceramics for Solid-State Lasers". Journal of the American Ceramic Society 78: 1033. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1995.tb08433.x.

- ↑ Ikesue, A (2002). "Polycrystalline Nd:YAG ceramics lasers". Optical Materials 19: 183. doi:10.1016/S0925-3467(01)00217-8.

- ↑ "Toxicological Overview of Amorphous Silica in Working Environment". http://www.degussa-nano.de/nano/MCMSbase/Pages/ProvideResource.aspx?respath=/NR/rdonlyres/1E02FAD4-E5D6-4CE2-8E5C-E19F4DAC7838/0/Toxicological_Overview_Amorphous_Silica_in_Working_Environment.pdf.

- ↑ Rondeau, V; Jacqmin-Gadda, H; Commenges, D; Helmer, C; Dartigues, Jf (2009). "Aluminum and silica in drinking water and the risk of Alzheimer's disease or cognitive decline: findings from 15-year follow-up of the PAQUID cohort.". American journal of epidemiology 169 (4): 489–96. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn348. PMID 19064650.

External links

- Tridymite, International Chemical Safety Card 0807

- Quartz, International Chemical Safety Card 0808

- Cristobalite, International Chemical Safety Card 0809

- amorphous, NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- crystalline, as respirable dust, NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Formation of silicon oxide layers in the semiconductor industry. LPCVD and PECVD method in comparison. Stress prevention.

- Quartz SiO2 piezoelectric properties

- Silica (SiO2) and Water

Media related to Silicon dioxide at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Silicon dioxide at Wikimedia Commons Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Silica". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Silica". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||